The Space Laser Dilemma: Asset-based financing for climate companies

Exploring the next frontier in Cli-Fi

Welcome to Climate Drift - the place where we dive into climate solutions and help you find your role in the race to net zero.

If you haven’t subscribed, join here:

Hey there! 👋

Skander here.

Mairi is back with her Cli-Fi (climate finance) playbook today, taking us even further into the money labyrinth with a story that sounds straight out of sci-fi: asset-based financing… and space lasers. (Yes, really!) Turns out figuring out what a used battery (or a used satellite) is worth is not as easy as it sounds.

But it could be exactly what climate entrepreneurs need to scale their solutions without drowning in VC equity or venture debt. Which are also harder to come by in the current funding ice age.

🌊 Let’s dive in

Did you miss the first chapter of her cli-fi playbook on how the climate capital stack has evolved? Check it out here:

🚀 Want to make an impact?

The 4th cohort of our accelerator launches in March, and applications are still open (but spots are limited). If you’re ready to fight climate change, don’t wait:

But first, who is Mairi?

Mairi Robertson is Director of Asset Financing at Ezra Climate, where she develops innovative financing structures for energy transition investors and companies. Previously she was part of McKinsey's Climate Finance Practice, and is now (another) Australian based in New York.

The Space Laser Dilemma: Asset-based financing for climate companies

Every ClimateTech CFO eventually learns the same painful lesson: New technology may change the world, but good luck figuring out what it’s worth.

Space Lasers & Company: A tale from the frontier

Let’s suppose you are an investor, and you like to invest in impactful and meaningful things that are going to make the world a better place (and generate good returns). You know, EVs, batteries, that kind of thing.

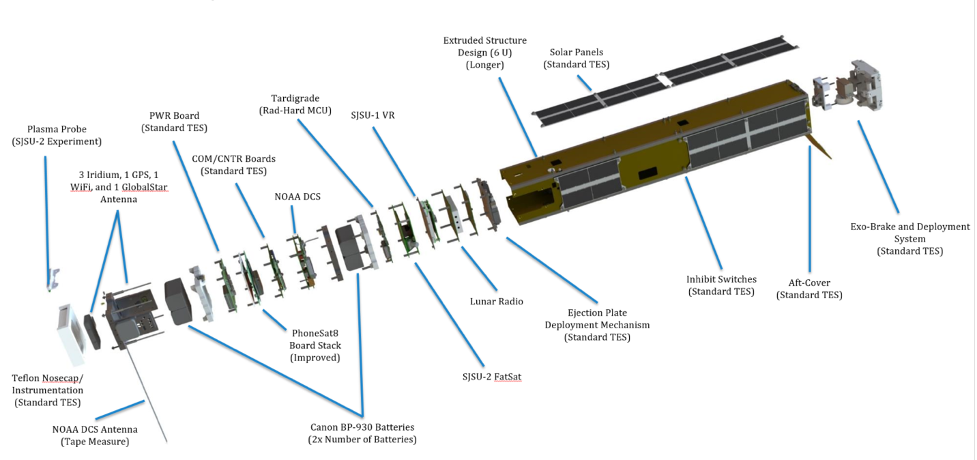

Now, let’s suppose a start-up — I’ll call them Space Lasers & Company (“SL & Co.”) — comes to you asking for money. They manufacture small satellites that use lasers to send solar energy directly from space to solar panels on Earth. The technology, they claim, can significantly increase the amount of solar energy that a panel yields. [1]

Their technology has passed lab tests and has had a successful first commercial pilot. The company itself is well-capitalised, thanks to a combination of venture capital and government funding.

The Conundrum

The CEO has secured contracts with a few solar farms who would like to sell the surplus energy their panels generate. The team will need to launch 100 satellites to execute on these contracts. Space lasers aren’t cheap (duh), so SL & Co. needs capital — and lots of it.

The CEO isn’t keen on venture debt (too expensive!) or raising even more equity (too dilutive!). She does, however, know about something called asset finance — that is, borrowing money which is lent against the value of the satellites she wants to finance. If the company goes bust, the lender would have the right to repossess the satellites.

Theoretically, this is a great option. The thinking goes like this:

Venture debt is expensive. Start-ups have a high risk of going bust. If they do, then by definition there isn’t much cash in the bank for the lender to recoup towards their original loan. Also, there are probably other parties laying claim to the company’s assets. High risk to the lender means a high cost of capital for the borrower.

Asset financing reduces this risk. The lender directly has a claim over the asset they are lending against. If the company goes broke, they can go and sell the asset to someone else, and make most of their money back. Less risk to the lender means they can offer a lower cost of capital to the borrower.

So far, so good, right?

Unfortunately, for the lender this isn’t quite so straight forward. When the asset in question is a space laser, his thinking will go something like this:

“If SL & Co. goes bust, then I’m going to be stuck with a bunch of, er, space lasers. What on earth (ha ha) are these worth? And would anyone actually be willing to buy them from me?”

The whole point of using collateral to lower the lender’s risk is redundant if the collateral has no obvious value.

This is what I like to call the “What’s This Worth?” problem. And it turns out it’s everywhere in ClimateTech — not just with space lasers.

The Asset Financing Blues: A brief history

Different industries have tried to get around this problem before. Back in the 1980s, Silicon Valley figured out how to finance semiconductor equipment amidst a desperate manufacturing war with Japan. Their secret? Financing production against purchase orders from future customers.

Biotech took this even further in the 1980s and 1990s. They developed IP-based financing and milestone-based validation frameworks because, turns out, it’s hard to value a drug that might not work. (Who knew?)

But ClimateTech adds its own special sauce to the problem. Take Direct Air Capture facilities — you’re trying to value:

Technology that’s never been deployed at scale

Revenue from a market whose demand is still untested

The value of carbon credits for a market that barely exists

The reliability of tax incentives that just got invented (and might get taken away, but maybe not, who knows!)

No pressure!

How deals are getting done

Despite all this, asset financing deals are increasingly happening in the ClimateTech market. Lenders are using creative term sheet structures in order to do this. Some of the approaches I’ve seen include:

The Component Game

Smart investors are breaking down novel technologies into their known and unknown parts and figure out what they can infer about the value. It goes something like this:

Known Components in each Satellite (65% of bill of materials):

Standard satellite bus systems (“I see there are secondary market transactions, and a kind-of-believable depreciation curve”)

Power distribution units (“That’s so commoditized, I’d be willing to bet a small fortune on what it’s worth in a year”)

Communication systems (“Hmm, I can dig up some comps that are decent estimates of what this might be worth down the road”)

Novel Elements of each Satellite (35% of BoM):

Laser transmission system (“?”)

Custom optical components (“??”)

Proprietary pointing mechanism (“???!!…What…is this? I guess it…points?”)

The underwriting conversation then becomes more nuanced:

Lender: “Okay, 65% of your bill of materials has established salvage value channels. We’ll advance against that at standard LTVs, adjusted for space deployment deterioration. [2] The proprietary components? That’s what your equity is for, pal.”

The Performance Guarantee Dance

Suppose Space Lasers and Company want to launch 100 satellites. A traditional lender would look at this and say “I have no idea what these are worth in liquidation. Hard pass.”

But creative lenders are doing something different. Here’s what a term sheet might look like from a slightly more ‘out there’ (sorry) lender:

Phase 1: Initial Deployment: Let’s take this slow. We’ll loan you 40–50% of the satellite value, and we’ll want to see basic operational metrics, component-level performance, and insurance coverage verification. You’ll take on the remaining 50–60% of the cost, and carry the risk that anything goes wrong.

If the company has met all the requirements, then they would proceed to a new arrangement:

Phase 2: Performance Validation: Looking good. How about we lend you 60–70% of the satellite value since you have a year of operating history, you’ve met some efficiency targets, customer acceptance testing is complete, and there aren’t too many warranty claims.

And, again:

Phase 3: Commercial Scale — to the moon!: Okay! We’ll lend 70–80% of the satellite value, so long as you maintain some proven operating margins, you’ve established some maintenance protocols, you can point me to some clear secondary market activity, and we’ve got several deployment cycles under our belt.

(Oh, and by the way — you miss any of those targets? The rate drops back down and you better dip into your equity, buddy).

This is clever: The lender’s risk drops as the technology proves itself; each milestone creates real data about asset performance (and thus value); and the company builds a track record of operating history that future lenders can underwrite.

You could imagine ways that this plays out in ClimateTech:

Battery companies getting better terms as they prove out a unit’s cycle life

Heat pump manufacturers unlocking more debt as they demonstrate a device’s durability or system performance

DAC facilities increasing leverage as they hit carbon capture targets

The key is picking milestones that directly correlate to asset value. Equipment uptime? Good milestone. Number of cool Wired articles published about your space laser? Unhelpful for underwriting.

The Corporate Backstop

This one is the easiest. Remember that BlackRock/Occidental direct air capture deal? Having a major oil company’s balance sheet in the background sure helps solve the problem.

Need a quick refresher on the Oxy deal? We have you covered:

The corporate backstop isn’t just about deep pockets, though. When a major corporate stands behind a novel technology, they’re often solving multiple valuation problems at once:

They’re usually the anchor customer (solving the revenue uncertainty)

They have the expertise to evaluate the technology (making other lenders more comfortable)

They can repurpose or redistribute assets through their existing channels (creating a pseudo-secondary market)

They might even have experience with similar technology deployments (providing those elusive comparables)

This is how the US Department of Defense helped spur semiconductor financing in the 1980s.

I’m seeing this play out across sectors. Steel companies backing new hydrogen technologies. Automakers standing behind novel battery chemistries. The pattern is clear: when traditional industry puts their balance sheet behind ClimateTech, asset financing gets a lot easier.

Of course, not every space laser company can find their perfect corporate partner. And there’s always the risk that your corporate backstop has their own problems—just ask the Volkswagon and Scania folks backing reccently-bankrupt Northvolt.

Oh, what’s a space laser CEO to do?

Lenders have a lot of say in the process. But companies can increase the odds of working around the “What’s This Worth?” problem:

Start small

Begin with corporate debt, venture debt, or (god forbid) equity for initial deployments

Build up real performance data (i.e., show me the thing works)

Create a secondary market (even if it’s tiny)

Be creative with structure

Use hybrid instruments that blend debt and equity (and be prepared to flex on advance rate over time)

Build in technology performance thresholds

Create clear milestone frameworks

Layer your capital stack

Use expensive capital for the risky pieces

Bring in cheaper capital as you prove things out

Keep your options open for refinancing

…And, lastly, some expectations management

With all of that said, we still can’t properly value used electric vehicles. That’s right — we’ve been making EVs at scale for over a decade, we have tons of performance data and there’s a huge market for them. And yet:

Nobody knows exactly how batteries degrade over time

Technology keeps improving, making old models obsolete faster

Charging infrastructure keeps evolving

The market — including suppliers, subsidies, and sentiment — keeps shifting

If we can’t figure out the value of a used Tesla, then maybe we shouldn’t feel so bad about struggling with space lasers. Or, put another way, it will take new technologies developing a track record of their own performance and value — i.e., becoming less new technology, and more boring old asset — in order to have greater access to this kind of financing.

In the meantime, if you’re building something that’s never existed before, maybe keep your equity investors on speed dial. You might need them.

Questions? Comments? Violent disagreement about the value of a used space laser? Shoot me a message.

[1] Yes, this is a real thing — and there are more than a few companies pioneering approaches to this.

[2] I’m sure adjusting depreciation curves for equipment degradation from deployment in space is a pretty straightforward task. Right?