It's time for you to contribute to the Climate Commons

How open data and digital public goods power every climate solution

Welcome to Climate Drift - the place where we dive into climate solutions and help you find your role in the race to net zero.

If you haven’t subscribed, join here:

Hey there! 👋

Skander here.

We’re finally pouring billions into clean hardware and nature-based solutions. But what about the digital infrastructure that makes those solutions intelligible, replicable, and resilient?

If you’ve ever tried explaining open source to a policymaker (or its climate impact to a funder) you’ve likely seen the blank stares.

Open source doesn’t just power the internet. It quietly underpins almost every serious attempt to decarbonize and decentralize. It’s time we stop treating it like a nice-to-have and start backing it like the keystone it is.

In today’s deep dive driftie Alex maps where digital public goods already support real-world climate action, from satellite emissions maps to open-source grid simulators, and where funding, policy, and stewardship still fall short.

Whether you're deploying mini-grids in West Africa, launching a carbon startup in Oakland, or shaping climate finance in Brussels: open infrastructure is your invisible teammate. Let’s treat it like one.

🌊 Let’s dive in!

🚀 Curious about a career in climate?

Join us for a powerful 60-minute live fireside chat and Q&A with three top climate career coaches, who’ve helped hundreds of professionals transition into meaningful roles in climate.

This isn’t a sales pitch or fluff, just real, actionable insights from experts who’ve been there.

But first, who is Alex?

Alex Stinson is an open knowledge advocate who has spent the past decade at the Wikimedia Foundation, working at the intersection of community, technology, and networks that leverage Wikimedia to address broader social issues such as climate change, human rights, gender equity, and cultural heritage.

In the aftermath of Trump’s first election and during the lead-up to the COVID-19 pandemic, he transformed a passing interest in food systems and environmental issues into a more focused commitment. As a volunteer, he helped update and organize the WikiProject Climate Change community and sought to expand the volunteer-led conversation about sustainability within the Wikimedia Foundation.

In 2021, he was one of the organizers behind the Open Climate collaborative. The group’s focus was on how a more open, equitable, and decentralized approach to climate knowledge (particularly in the Global South) can lead to more inclusive, diverse, and just climate action. This work has continued in various forums, largely supported by groups such as Creative Commons and the Open Environmental Data Project.

It's time for you to contribute to the Climate Commons

This is another long one. Click on the headline to read the full deepdive 👆

Climate Tech needs to grow the role of Digital Public Goods for Climate Action

I think it's time for you, dear readers of Climate Drift, to invest in Digital Public Goods for Climate.

Yes, if you are reading the Climate Drift publications you are probably either building a climate enterprise, funding one, or trying to find the next big idea to address the climate crises.

You are probably already familiar with the larger systemic problems driving the climate crises: slow institutions; captured media, economic and political systems; dependencies on scale-focused industry that woefully neglect their externalities; etc.

But except in a few contexts (ahem, China) there are not going to be many top down solutions. As journalist Rachal Donald of the Planet Critical podcast is fond of pointing out: it's not so much about scaling up solutions, but rather scaling out so that geographies and communities can choose to deploy solutions for additional resilience and autonomy. We want 10,000s of enterprises that work at regional or local scales to deploy climate technology (especially if dismantled government infrastructures and economic nationalism becomes the new norm, ahem, Trump and Milei).

How do we ensure that the decentralized system of solutions creates the most impact? When climate impacts and solutions need to be deployed globally, with the greatest decentralization and impact, how do we make sure that digital tools don’t get in the way of deployment?

I have been building communities around open data and Wikipedia for the last fifteen years, and, for me, many of the problems could be solved by open source projects or what most international forums are calling Digital Public Goods.

What does it mean to work in the open, especially in a competitive marketplace?

Digital Public Goods are open tools (data, software, systems or repositories) built on the principles of Open Software and the subsequent Open Movement. Arising in the early days of the internet, the open movement operates on the principle that the bulk of the world's knowledge—its many digital libraries, art galleries, data sets, and software to access it—are meant to be shared. This sharing is meant both in the legal sense (free as in speech) and economic sense (free as in beer). The shared legal foundations for making knowledge open is through removal of copyright through open licensing (see this explainer by Creative Commons) or removal of other intellectual property restrictions, such as open software licensing which allows developers to reuse previously built code (see the Open Definition).

The open movement has produced some of your favorite technologies: the Internet, Wikipedia, Wordpress, and Android are all open source. A 2023 estimate suggests that 96 percent of software has open source components. Most of the internet is run on open infrastructure (most websites not selling something use Wordpress, Drupal or other open systems), and your tech stack at your business has dozens of open software components. In almost every new tech ecosystem, open just makes things easier. For example, the majority of AI systems have a strong knowledge backbone from open data.

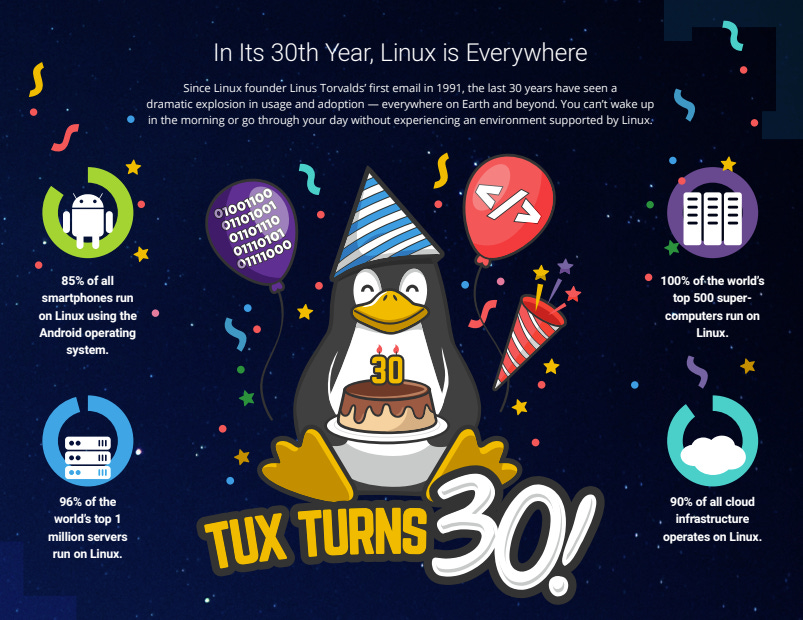

Open source technologies are infrastructure for almost every field of computing. For example, the widespread adoption of the Linux operating system is why almost every sector has dozens of small tech organizations that build sector-specific computer systems. A Microsoft or Apple operating system is not so great for creating a checkout system for your local grocery store, but almost any small tech organization anywhere in the world can create a Linux-based operating system to solve that problem. As the Linux Foundation noted in its 30th birthday celebration in 2021 is literally everywhere.

Though software has been the most business-visible success of the open movement, much of society has been shaped by open movement as well. Using the Creative Commons license (i.e. CC-BY-SA) many knowledge sectors have a significant “open” backbone. In the early 2000s the open access approach expanded to a lot of other sectors: from creating educational materials that anyone can use (Open Educational Resources), licensing media at cultural institutions like museums (Open GLAM), academic publication (Open Access to Science) and outputs from governments (Open Government Data). These goods allow broad Digital Public Goods that act as shared utilities like Wikipedia or Open Street Map, but also allow everyone everywhere a basic amount of access to knowledge without fear of commercial barriers.

As first a volunteer and then working at the Wikimedia Foundation for the last 11 years, I have focused on what that open knowledge means for public communication and access to culture and critical knowledge. As the 8th largest website, Wikipedia operates in over 300 languages, and has contributors around the world: this has given our community incredible leverage for convincing institutions to share content freely. In 2009, one of my first volunteer organizing activities (at age 19) was focused on helping Smithsonian staff think about their open access policy. After ten years of steady advocacy by a larger network of collaborators, we managed to secure an open access policy for the entire digital collection (nearly 3.0 million images at launch) of the Smithsonian free of copyright restrictions as open data. Institutions like the Smithsonian, often have knowledge relevant to the world -- contributing that content and data to be freely reused almost it to illustrate nearly every language Wikipedia. Now the world’s heritage is far more easy to share online, and is being used to create digital culture and science projects in innumerable ways.

Government procurement policies and recent international policy changes towards open software and open data has created a sea change in demand for Global Digital Goods:

In Europe, the open movement has been very successful at leveraging open software, data and science as part of policy measures -- making them the default in a number of fields. There the implementation of open is not only beneficial from an egalitarian access perspective, but also creates more space for economic and social activity that otherwise do not exist.

Similarly, implementing open in the Global South allows for more efficiency in government spending than relying on closed access, proprietary technologies.

The UN in it’s implementation of the Digital Global Compact, has been investing in the Digital Public Goods Alliance as a way of ensuring equitable access to these foundational tools.

At the same time that the opportunity for using Digital Public Goods is growing, it's also very challenging to build these projects from scratch in the current technological environment. Unlike the enthusiastic early days of open data or open data in science, just building the open systems and expecting others to contribute no longer works. Wikipedia, Open Street Map, and other early open, collaborative projects were built before the immense amount of competition for attention in digital technologies (hello ever scrolling social media apps and never ending video streaming!).

Throughout this paper, I am going to highlight how different business models are emerging in the context of Digital Public Goods, but to do this well would require an entirely different Climate Drift post!

Open, Digital Public Goods and Climate

When thinking about the role of “open” and Digital Public Goods in the climate crises, there are two broad areas where these concepts could be applied: to the science of climate change, and to the broader climate solutions space.

Work on open access to climate science has been fairly robust: the vast majority of philanthropic and government funding for science is covered by open access policies. Moreover, the 2021 UNESCO recommendation on Open Access to Science demonstrates a growing consensus among governments and policy makers to continue that practice.

The shift towards open access to climate science is not complete: for example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report has restrictions on its reuse and much of its citations (the most important climate science according to a panel of experts) is behind a paywall . These paywall restrictions mean that the science is only accessible if you can pay exorbitant fees. For the most part, the scientific community has a clear consensus on how to solve this: publishing in a journal that supports open access (both free to read, and free to redistribute). Moreover, most international recommendations from UNESCO and others state that research and data should be published in restriction-free publications.

As I talk to people involved in financing climate projects: many financiers of these projects are either hiring desk researchers to evaluate projects, paying for expensive paywalled services (i.e. the Bloomberg Terminal type service for their particular sector or even just the paywalled science publications), or repeating the kinds of desk research that non-profits are already doing. This kind of redundant investment would be better served by investing in shared Digital Public Goods.

For business leaders, the more important data is largely not scientific data, but rather data that can drive decisions about the marketplace and the possibility of implementing climate solutions. Without shared data about supply chains, contracts, economies, infrastructure projects, financing and regulatory environments, it's hard to invest.

Moreover, open data and Digital Public Goods are critical as the world becomes more complicated, as we navigate both climate impacts and the unexpected effects of rapidly deploying new technologies. For example, in the recent blackout in Spain and Portugal, experts and businesses like journalist Javier Blas were actively looking for credible data about the grid operations. In that absence, unverifiable narratives blaming renewable energy for the blackout quickly spread.

Beyond Energy, the climate crises requires us to rebuild systems and technologies across society. If we want to move quickly across all sectors -- we will need to think about how open data and Digital Public Goods can speed up climate solutions in every sector.

Where Climate Open Data is Already Beginning to work: Energy Infrastructure

The energy sector is a good place to start, both because of both it’s long history of collaboration around data sharing and standards, but also because most energy providers have regulatory requirements for publishing open data. However, just because there are a lot of incentives for creating open data about their operations, it doesn’t mean that is usable data (or that the underlying software producing that data is transparent, or consistent). This is where open data projects have stepped in!

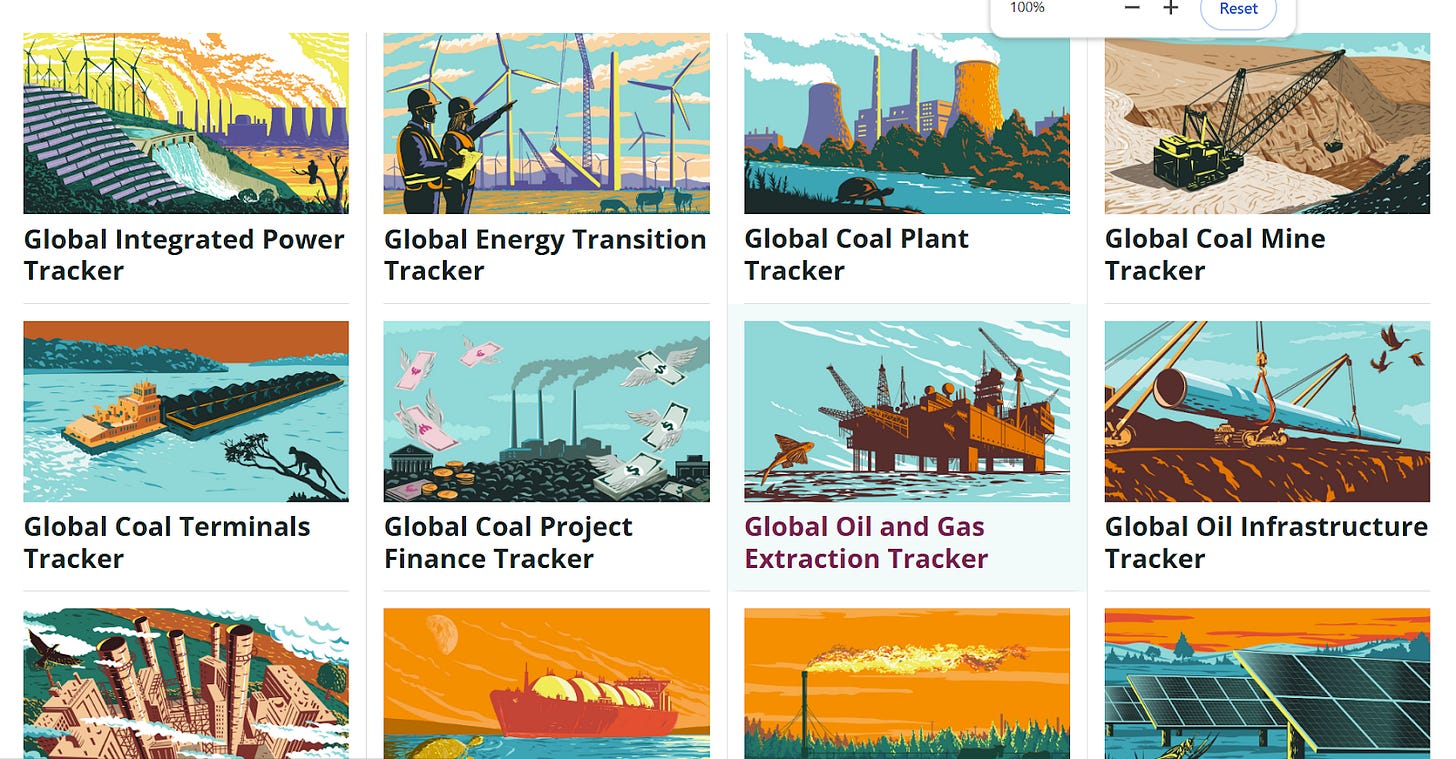

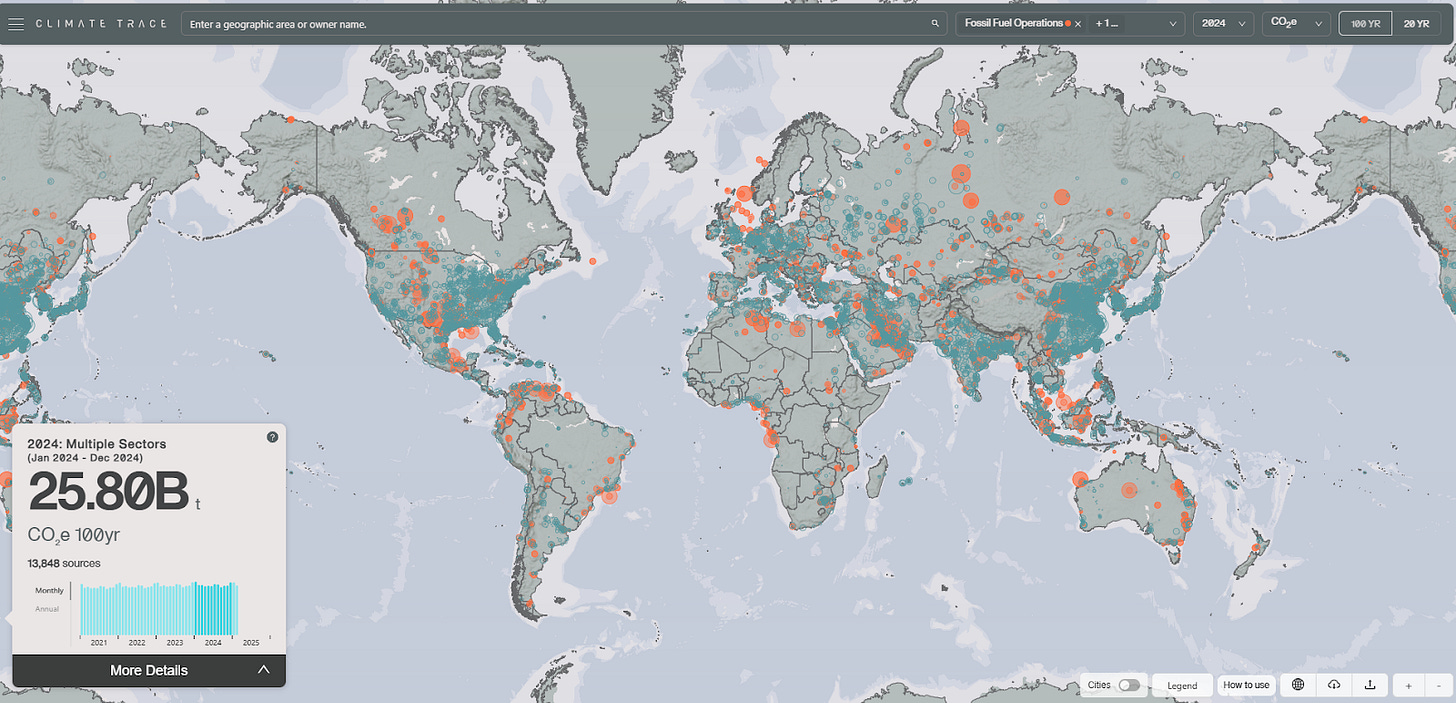

One of the best datasets about the current energy infrastructure ecosystem is the Global Energy Monitor. As a researcher led dataset, published as open data: researchers and international actors like the IPCC, IEA and others to better understand energy sectors being deployed, operated and retired. This work allows for a number of reuses, such as reports by the IEA and IPCC, and development of a map of Energy infrastructure as part of Climate Trace. By using the Creative Commons license on the data, and providing this data with limited barriers, Global Energy Monitor has become the default standard for both non-profit and for-profit analysis of the global energy sector.

This kind of open access to data about energy infrastructure was not the default until recently. Before 2022, The International Energy Agency only published its reports as a pay service. Data and research published as open access has been a core pillar of Dr. Fatih Burtah’s strategy to create an IEA that supports the energy transition (in part instigated after an extended campaign by Our World in Data and other non-profit initiatives ).

Even when open, often the official data coming from governments, public utilities, and transparency processes can be nearly unusable. For example, the country where I live, Uruguay, has one of the most advanced open government data strategies in the Latin America. Yet, effectively reusing their energy sector data requires deep contextual knowledge about how to interpret spreadsheets with limited documentation. In effect the data is open, but obscured for the average person seeking it and only reusable when aggregated by projects like Global Energy Monitor.

Especially when working across jurisdictions, or trying to synchronize complex diversity, aligning on an open-source software solution creates better practices. Recently, the non-profit Open Energy Transition (OET), has been growing rapidly to focus on energy grid planning consultancy services that expands open software used by academic institutions and open data infrastructure like OpenStreetMap. As the energy transition accelerates interconnection, grid development and long term planning all require aggregation of disparate sources of data and specialized analysis. OET is centralizing this expertise, as a maintainer of an open source toolkit that then can be used by anyone else.

There are a number of other technical initiatives driven by open source software in energy,

A 2023 survey of the energy sector already found more than half of the sector was adopting Open Source Technologies to drive greater ease of technical system implementation.

The Linux Energy Foundation is convening grid operators and a number of software providers to collaborate more on the expansion of Open Source for Energy Infrastructure.

RMI is supporting the Virtual Power Plant Partnerships (VP3) use of open standards and open source software.

The Centre for Net Zero supported by Octopus Energy is producing synthetic customer data software for smart meters that could be an industry standard for privacy and security.

Open Climate Fix is building open AI forecasting software that can strengthen the overall resilience of the grid.

I am sure there is more (I am a relative novice when digging into the energy tech stack). But as I look to other sectors working on climate tech, I am having a far harder time finding the Digital Public Goods that could be driving change.

Other bright spots in Digital Public Goods for Climate

Besides open science and energy, I think the expansion of other sectors using Digital Public Goods that will be fundamental for climate action.

The Climate Trace Coalition is creating a global public dashboard and map of CO2 emissions independent of government data. The coalition was formed in 2020, and it recently reached a significant milestone of nearly live tracking of global emissions. Part of what makes the collaboration between the partners more successful is that they are all contributing open data and tools.

One member of the coalition is Earth Genome who built the map layer for Climate Trace. One of their main projects is developing an AI base model and global search tool, called Earth Index, that will make it easier to search geospatial phenomena to track environmental issues (such as unregistered gravel pits in the Balkans, or illegal airstrips used for drug trafficking in Peru).

The Earth Genome team has strong roots in the Open Data community. Their team actively contributes to open source tools for geospatial AI, including but not limited to:

publishing a open methodology and data set to create AI interpretable tiles for the whole world;

contributing to underlying software layer for geospatial AI; and

Searching through the methodologies and contributing organizations for Climate Trace: all rely on open licenses, scientific data that has been published as part of government or open science funded initiatives, or other organizations that publish in the open.

Similarly, Source Coop is an initiative by Radiant Earth to support storing this environmentally inflected geospatial data, and rescuing some of the Open Data that might be disappearing as part of the US Federal government contraction.

There is also a lot of similar work happening in adjacent environmental issues, such as around biodiversity (i.e. projects like iNaturalist and Biodiversity Heritage Library), supply chains (i.e. Open Supply Hub), toxins in building materials (i.e. Habitable Future’s Pharos database), and many more.

These bright spots are particularly important in light of the Trump Administration’s approach dissemination of public data sets and science. The US Government’s long history of publishing weather, satellite, and scientific data in its public domain license has made it a backbone for public investigation of environmental issues and documenting environmental history. Most Americans check the weather several times a day, and the 301 billion forecasts made by NOAA and its partners its critical for protecting infrastructure, insurance farms and economic futures markets. Yet, under Trump, the United States Government is willing to destroy, or significantly alter the regularity or accuracy of the data. Just because some of this data is being rescued by archivists, doesn’t mean it’s going to be accessible in the ways we need it to solve problems in climate tech.

If you are working on Climate Tech, you can help change the movement

As the Global Digital Compact emphasizes: the sustainable development goals (including SDG 13: Climate Action), require technologies that can be used by anyone, and especially low and middle income countries.

However, just creating policies for open software and data doesn’t always solve problems. Often the creators of open communities are not thinking about user experience, especially for resource constrained users like small businesses or communities in the global south. Rather, it requires an ecosystem of investment that brings those Digital Public Goods into the hands of the reuser.

As someone who has been part of open movements for over 15 years, there are at least three areas where I think there could create more clear climate oriented best practice:

Using philanthropic and mission driven capital open access policies that encourage enterprises to create Digital Public Goods

Building sustainable business for stewards of Digital Public Goods

Aligning industry association standards and policy environments designed to fill this Digital Public Goods with data

Option 1: Build Philanthropic and Mission Driven Capital Open Access policies

Much of the capital coming to early stage companies in Climate comes from investment firms, philanthropies, coalitions, offtake contracts and other purpose created capital with clear climate impacts in mind. If we want to address the climate crises, we need to invest in increasing the speed of scaling deployment of technologies. Most of the funders that I have read about already acknowledge this problem -- however, there doesn’t appear to be a widespread understanding of how open data or Digital Public Good policies can help with that process.

If our larger thesis is that the climate business need to scale up and scale out: early adopters need to lead the way in sharing knowledge for subsequent organizations. Mission-based and philanthropic funding going to new enterprises should incentive sharing learning in public.

One thing that I have yet to find as I am onboarding into the climate tech sector is a clear documentation of Open Access policies best practice for philanthropic capital focused on climate. (Send me one if you know about it).

Philanthropic climate funders could require open science, data and procurement practices in exchange for favorable funding conditions. For instance, funders could offer more favorable conditions for financing (i.e. better interest rates, top up grants, data publishing provisions etc) for adopting open practices.

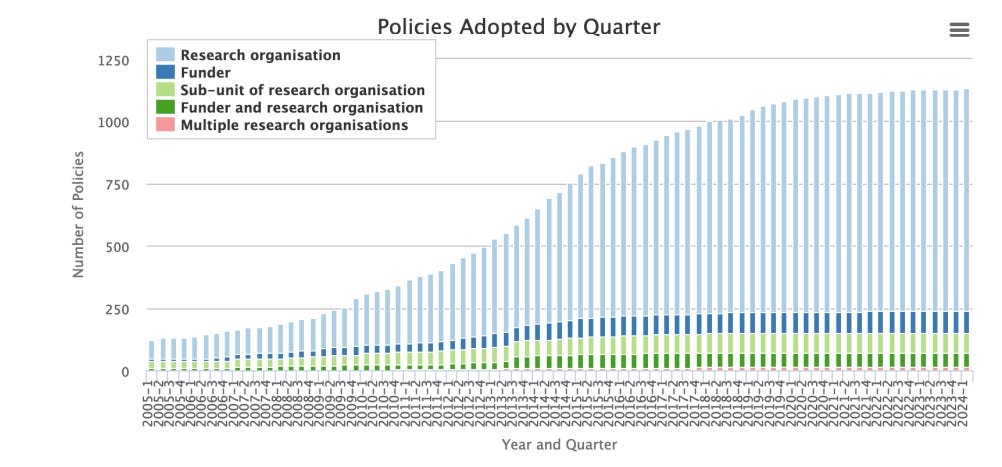

The best example of this kind of funder-based transformation of information environments is in open access science and publishing: as funders understood how open access furthered their goals to create science for public good, they adopted Open Access Policies. Declarations like the Budapest declaration on Open Access and subsequent networks of funders like the Open Research Funders Group, defined best practices that allowed science funding for open access publishing. These funder policies often require the funded individuals to publish their findings in an open access journal or deposit those findings in an open access research database. In the process researchers and institutions get additional funding for implementing the practice (usually to pay article processing charges, or other kinds of open infrastructure support fees).

Some businesses are taking an open access approach already. The coastal carbon dioxide removal startup Vesta is an excellent example of a public good approach to an enterprise with diverse funding. The science and technology of rock weathering has little direct commercial value alone (it combines widely understood practices in science, mining and beach restoration). Vesta has published all of its scientific output and business processes as open access. This allows future enterprises to replicate the business model in a way that is appropriate for the local environment and economies.

In some sectors opening data is already happening, because the underlying technology relies on basic science (i.e. carbon dioxide removal based on rock weathering and biological process), or provides competitive advantage through open practices (i.e. the move by Tesla to release their charging plug technology to have influence over the market or the Virtual Power Plant coalition hosted by RMI).

However, if we want to decentralize the technologies required for a network of project-developer type enterprises to succeed (especially in new conditions and in the Global South), we need not just foundational science to be open but knowledge about the entire implementation pipeline. In an environment where both philanthropic and for-profit funders want metrics and evidence of success of projects in different contexts, sharing widely available data about the business ecosystem is a necessity. Sharing it as open data and making it usable as Digital Public Goods, can all start with funder policies.

Option 2: Building sustainable business for stewards of Digital Public Goods

When I took the Airminer’s Bootup in the beginning of the year, a perpetual point of reference for the course was CDR.fyi: https://www.cdr.fyi/ . In theory this is a great project: builds transparency in a rapidly changing sector, with evolving standards and practices.

However, at the core of the business model is a transactional relationship with both information providers and information consumers that emulates the business model of the Bloomberg terminal. In order to consume or share the data in the marketplace to make business decisions, you need to pay. For the carbon marketplace, where there is a fair amount of available capital at the moment and most companies are working from the Global North, spending a few hundred or thousand dollars on a software or data service company may seem reasonable.

But if that same data is unavailable in a free to access format, we are leaving most climate motivated communities out of the work. As we have learned with scientific publishing: even a few limited fees or other friction quickly makes it impossible for institutions in the Global South to participate in that science. Relying on a “purchase a service” model of access to data or participation in industry learning initiatives, quickly closes off participation. What do you do with these increased stewardship or maintenance cost for providers of data services? We need to evaluate funding agreements so that they anticipate the additional cost of paying a steward to maintain open data and software.

The best way to “work in the open, but pay for the stewards” is to develop more service providers focused on stewardship. As I mentioned earlier, one example of a business that has been growing rapidly on this model is the Open Energy Transition consultancy. Their model is based on open software developed in universities for energy modeling and open data ecosystems like OpenStreetmap, Wikidata, and Global Energy Monitor. In European markets, Digital Public Infrastructure projects for governments using open source software have spawned coalitions of consultancies caring for Digital Public Goods used for regional, national and local government infrastructure (read the report here). Earth Genome is providing a similar consultancy model while also providing pay services for its core business, Earth Index.

For large, global data sets that drive international software, industry collaboration to create open tools has been common practice for a long time. For instance, MapBox has long invested in OpenStreetMap, and the mapping industry has recently built the Overture Map Foundation in order to mix OpenStreetMap data with other sources (some of it generated from AI).

One of the challenges with open projects is that they often rely on the goodwill of actors within the larger sector to get started (i.e. charitable funding), but, as they mature, it becomes harder and harder to provide ongoing sustainable funding (after all you already built something that is available for free! But maintenance is expensive...).

In this funding environment, Nonprofits working on open data can enter into several traps: such as becoming a donut organization, where the only way to maintain the core service (the donut hole) is to add more and more extra projects on the edge (the main part of the donut). Unfortunately, with this kind of approach the donut slowly grows bigger, away from maintenance of the core services. Another common problem is not having a long term plan for maintaining the software once core contributors have to step away for career or life changes.

Starting in the late 2010s, there has been a growing number of organizations trying to address this maintenance vulnerability in Open Source Software. Such projects not only leads to neglected shared resources but critical security vulnerabilities.

For some sectors, funding for open source software maintenance has come through philanthropy, like the Chan Zuckerberg Invest in Open Scientific Infrastructure fund or for the library and research sector the Invest in Open Infrastructure Initiative is providing structured funding for investment and maintenance of infrastructure. Alternatively, in open source software, several organizations, such as the recently acquired Tidelift, directly pay open software maintainers for downstream reusers.

Critical knowledge projects, like Climate Trace, for example, have real risks in becoming flash-in-the-pan projects when funders, partners or infrastructure providers divert their attention to other problems.

We also want to avoid open projects becoming too dependent on individual patrons. The hyper-concentrated role of the US Government in creating open access scientific data around medicine, climate and public health means that the current administration's approach to purging data from the CDC, NIH, EPA and NOAA puts many open projects at risk.

Climate tech organizations, and their funders, should be prepared to help these Digital Public Good organizations become sustainable, outside of the purely philanthropic or government sponsored funding streams.

Option 3: Leveraging regulation, certifications and standards to normalize data commons

Marketplaces seeking to create efficiencies could rely on regulations, standards or policy to instigate the use of data commons and open standards.

As I mentioned earlier, the energy sector has tried to create a number of open standards to solve key problems where interoperability requires ease of integration. This is similar to how the internet has relied on open source protocols and software to make the ecosystem more resilient.

When open standards are required for regulation or certification, this creates a natural landscape for collaboration on open data or open source technologies.

For example, the Pharos hazard chemicals database from Habitable (formerly Healthy Building Network) is a direct response to building code certification like LEED from the US Green Building Council. Builders like Google wanted their architects to invest in building materials that met non-toxic standards. To do this, they paid for building more data on Pharos. As that database grew, it has allowed other applications such as manufacturer Klean Kanteen to remove toxic chemicals from its manufacturing supply chain.

Similarly, the European Anti-Deforestation Law in Europe has increased demand for supply chain data significantly. Because big brands and manufacturers need to report if their supply chains could implicate deforestation regions, they are suddenly looking for more information about their suppliers. This is where Open Supply Hub starts to kick in: by crowdsourcing the basic data about these suppliers (through support from consultants, companies and non profit initiatives), they are able to create a more valuable resource than if companies (or expensive consultancies) had to build out the data system. This open data layer then allows for more complex unexpected analysis, such as what parts of the supply chain were affected by the March 2025 earthquake in Myanmar or the January 2025 fires in Los Angeles.

As other European and Global South regulations kick in (such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism in Europe), we have real opportunities for the coalition of consultants, software as a service organizations, and professional associations to make open data or other Digital Public Goods the standard.

Non-profit or professional organizations are necessary for aggregating and redistributing the open data as useful systems. Even though the data can be free, a pay for data business model to help support these organizations: for example, Enterprise-focused API use plans can incentivize payment for first-in-line use of the data, while also preserving a free front-end for the casual or less well resourced user. Here are some examples of these policies and plans: Open Supply Hub, and even Wikipedia. These funding streams don’t pay for the entire organization, but provide a base stream of funding. And, more importantly, these kinds of payment models increase maintenance oriented partnerships for the non-profits operating them.

In Conclusion

I think there is a world of opportunity for us, in climate tech, other pro-environmental technological sectors, and the funding ecosystem to think about how we take care of Digital Public Goods for building climate solutions.

As much as I am a long-term believer of open movement practices, there are a number of “traps” that startup open projects experience: funding shortfalls, customer-fit problems for data services, capture by bigger organizations, etc. These risks are real, and sometimes not as straightforward as those experienced by businesses going to market.

At the same time, the gap between haves and have nots in terms of implementing climate tech solutions is real, and building in the open, investing in Public Goods is the only way to speed up our collective action.

Want to get started! Here are some things you can do now:

Ask your tech teams to investigate Open Source Software or Data they can integrate (and help main). Here are some great repositories: https://opensustain.tech/ and https://climatetriage.com/

Take a look at the Digital Public Good Registry and identify what is not there and encourage your Open Source collaborators to join it. The Digital Public Goods Registry is still relatively new, and needs your help growing on Climate!

Did I miss an example of Digital Public Goods for Climate? Do you want to connect with me about your project? Reach out on LinkedIn

🚀 Curious about a career in climate?

Join us for a powerful 60-minute live fireside chat and Q&A with three top climate career coaches, who’ve helped hundreds of professionals transition into meaningful roles in climate.

This isn’t a sales pitch or fluff, just real, actionable insights from experts who’ve been there.